How user-centered translation improves usability

Published on

Author

Share

Originally posted by Eric Hutt of Neo Insight on February 14, 2018; Updated for DFFRNT, October 2023

Do word order and word count make French-language websites less easy to use?

From a UX perspective, the first few words of a heading, link, summary, or paragraph are critical. Francophone users are faced with longer pages, with less obvious headings and summaries, with keywords near the end of links rather than the beginning, and fewer capitalized terms to easily locate when scanning a page.

The solution is to apply UX best practices to translation. Involve your translator early in the design of content. Train your translator in writing better navigational pages.

Words are usually the most important content on a website. But not any old words will do. Words are there for a purpose. On most websites, words are there to help people accomplish a task; either to make a decision, buy a product, access services or find information.

In his book Killer Web Content, Gerry McGovern outlines several key considerations for developing content, with a particular emphasis on knowing your users’ tasks, and the language they use to understand those tasks. It follows that translated content on a website should also help users accomplish their tasks.

McGovern’s considerations do work; many of our clients have modified their web content to be more user-centric and have seen these changes help users be more successful at their top tasks.

In many of our usability testing and UX projects French-language websites don’t seem to test as well as their English-language counterparts.

The reasons for lower performance of French-speaking participants are difficult to pin down, but we have noticed a few differences between the English and French versions of websites which may contribute to this lower performance. Let’s examine three issues we’ve observed contributing to this phenomenon: content length, word order and capitalization.

1. Content length

We compared the total word count and character count of a few different websites on which we’ve done work in the past, comparing the English and French versions of the same page.

PageEnglishWords/CharactersFrenchWords/CharactersIncrease in French content lengthPage A472 words3385 characters663 words4575 characters40% more words35% more charactersPage B424 words3039 characters575 words3981 characters36% more words31% more charactersPage C241 words1569 characters314 words2185 characters30% more words39% more charactersPage D285 words1730 characters355 words2420 characters25% more words40% more characters

In this group of pages, the French versions had 25 to 40% more words, and roughly 30 to 40% more total text (as measured by character count). Larger amounts of text will generally have a negative impact on task performance as users simply need more time to scan longer pages. They also have higher chances of not finding the information they’re looking for.

Though French content may inherently need more characters or words, there are certain translation choices which can help minimize the increased length. For example, Le guide du rédacteur, from the Canadian government’s Translation Bureau, suggests the process of neutralisation to avoid having to write both masculine and feminine versions of nouns. (Le guide du rédacteur and Clefs du français pratique have now been combined to create a new tool called Clés de la rédaction.)

Words on a website should be measured not by their linguistic excellence or translation fidelity, but by the extent to which they help people achieve their outcomes."

Eric Hutt

2. Word order

Word order is intrinsically different between English and French. From a UX perspective, the first few words of a heading, link, summary, or paragraph are critical. The findings of the Eyetrack III study suggest that users only read the first few words of headings and summaries – and only continue reading if those first few words are engaging!

If an English version of a page has important keywords in its headings, but the French version has a different word order which shifts those keywords into the fourth, fifth or sixth position, then francophone users may not read them as frequently as anglophones. Similarly, users typically only read the first two words of items in a list, which makes those first words critical.

It’s hard to pinpoint to what degree word order alone may impact performance but based on what we know about page reading behaviours, it is quite likely that users on French pages aren’t seeing keywords as quickly, nor as often.

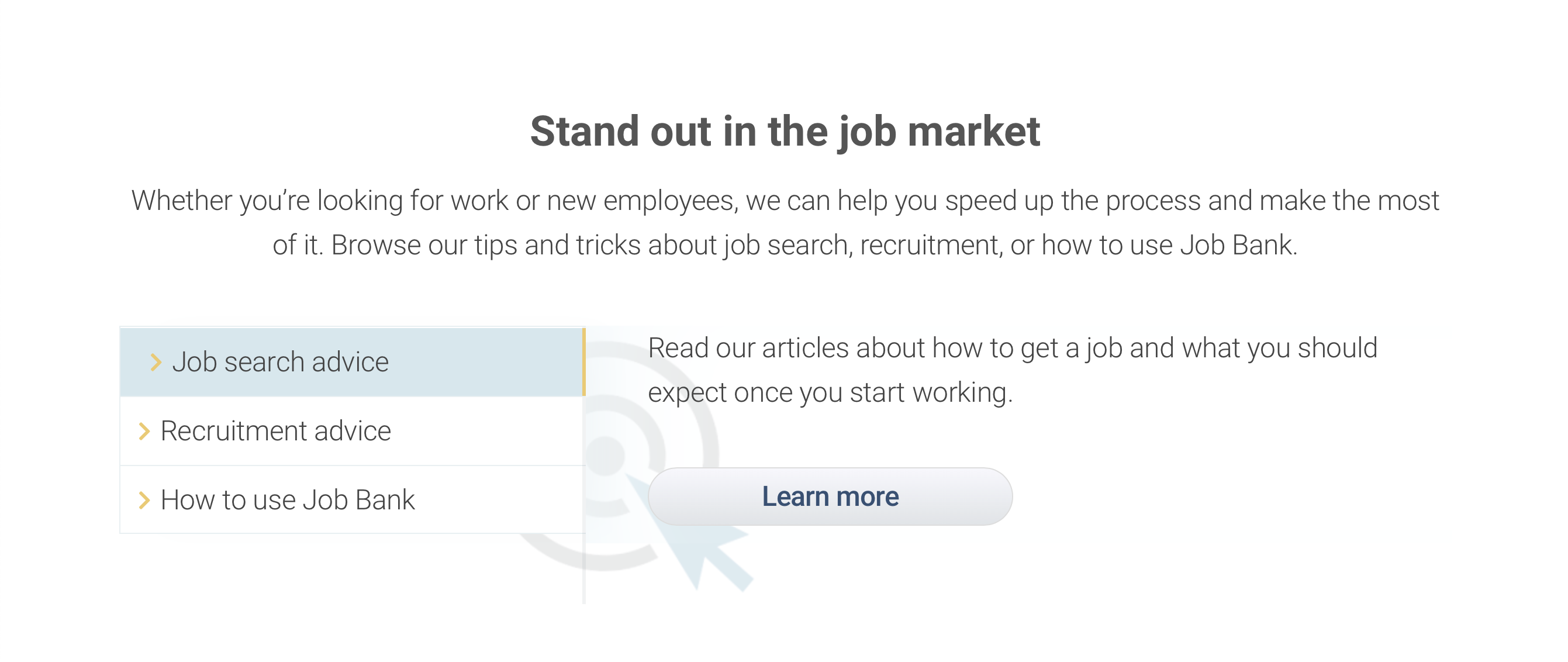

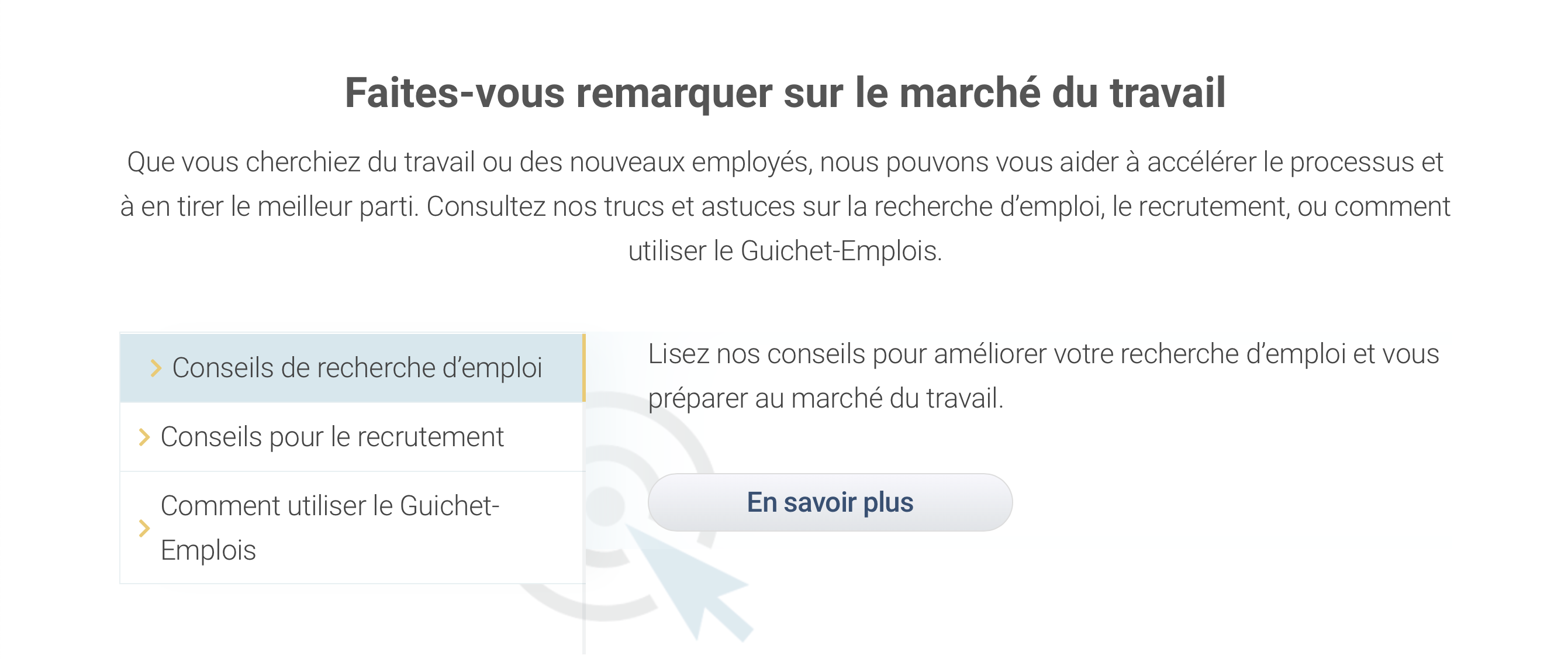

These examples from the Canadian government’s Job Bank website demonstrate the differences between English and French texts in terms of word order and work count.

Our Job Bank research is not related to translation, but you can read about it on our website.

3. Different capitalization norms

The federal government’s Le guide du rédacteur shows us that the French language capitalizes fewer words than English, including days of the week, months of the year, languages and nationalities. We’ve noticed that sometimes, the names of programs, events, funding opportunities, and other key items will have every noun in the name capitalized in English, but in French only the first noun (or none at all) will be capitalized. Le guide du rédacteur provides a good overview of how and when to capitalize words in French.

Capitalization is important for UX – it makes key words stand out and guides the user’s gaze to important sections of text, especially within paragraphs. With fewer capitalized nouns to look for, francophones may have more trouble quickly finding the content they need.

How user-centred translation helps

The above issues do not exist in isolation. Rather, French content is often impacted by all of the above at once. Francophone users are faced with longer pages, with less obvious headings and summaries, with keywords near the end of links rather than the beginning, and fewer capitalized terms to easily locate when scanning a page.

The struggles experienced by francophones during the bilingual projects we’ve tested may reflect a broader frustration with multilingual websites, possibly impacting a large segment of the Canadian population. Though the proportion of Canadians with French as their first official language spoken is slowly declining, according to a Statistics Canada infographic, it is still projected to remain at roughly 20% of the total population for the next several decades. Furthermore, the proportion of Canadians with a mother tongue other than English or French is expected to reach up to 31% of the population by 2036.

Linguistic diversity in Canada will drive a need for effective multilingual content – a need which must be answered with a cohesive UX strategy.

Developing best practices

Translations in any domain can have significant impacts:

- A nursing exam caused higher failure rates in francophone students (read the Radio-Canada story).

- A law with a single extra comma in the French version, shifted a court ruling (Rogers Communications case).

It’s important to always consider the purpose of the words being written and translated. On a website, that purpose is to help people accomplish a task.

The best academic translation from one language to another may not be the version that best helps readers achieve their goals. Words on a website should be measured not by their linguistic excellence or translation fidelity, but by the extent to which they help people achieve their outcomes.

Recently, the concept of user-centered translation has been proposed by Suojanen, Koskinen, and Tuominen in their book. They define UCT as a process in which “information about users is gathered iteratively throughout the [translation] process and through different methods, and this information is used to create a usable translation.”

Many things must be considered for truly user-centered translation, including some particularly critical steps:

- Defining, describing, and involving the end-users, possibly even before beginning the translation effort.

- Consideration of user mental models and how they impact translation and word choice.

- Evaluation and testing of the translation throughout the process, especially early in the translation to ensure that the translation is usable by the intended linguistic population.

- Involvement of the translator earlier in the process, in meetings with your team.

Other components comprise the full UCT framework, but these points above will resonate with any content creator or website owner looking to improve the usability of their website. Simply meshing long-held UX practices with translation efforts will go a long way toward improving outcomes. Translating English into French, or any other language, is not enough – the users must be central to the process of multilingual content creation at every step.

Special thanks to Sarah MacNeil, an Ottawa-based translator, for her advice and input into this article.

More reading:

- Killer Web Content, Gerry McGovern, 2006.

- Eyetrack III: What News Websites Look Like Through Readers’ Eyes

- User-Centered Translation, Tytti Suojanen, Kaisa Koskinen, and Tiina Tuominen, 2015.

.jpg)